Human Capital and the Rise of Women’s Economic Rights

There are many ways to measure growth in the Postbellum economy between 1865-1900. Some examine quantitative measurements of economic conditions such as the Gross Domestic Product (DGP). In contrast, others concern themselves with a more qualitative measure looking at the Human Development Index (HDI) created by the United Nations.[1] The main goal from either of these is to answer the questions: “Does improvement occur?” and “What significance does this have for American history?”

An examination of California and Montana in the late nineteenth century will show expansion in women’s economic rights due to the shifting roles of human capital

Given the nature of this subject, a qualitative methodology will prove apt in assessing how the idea of women as human capital led to growth in the economic rights of women. For this purpose, the works of Paula Petrik, Albert Hurtado, Matthias Doepke and Michèle Tertilt will help compare the growth of women’s economic rights in California and Montana throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century. First, Petrik’s 1987 article highlights the development of economic rights for women in two Montana mining towns between 1865-1907.[2] Next, Hurtado shows how the economy of the California gold rush led to varying roles of human capital, which resulted in an increase in women’s economic rights.[3] Lastly, Doepke and Tertilt cover the historiography of women’s economic growth in the United States overall and emphasize the ‘supply’ of rights by men brought on by the need for human capital.[4]

Why the need for human capital led men to give women economic rights

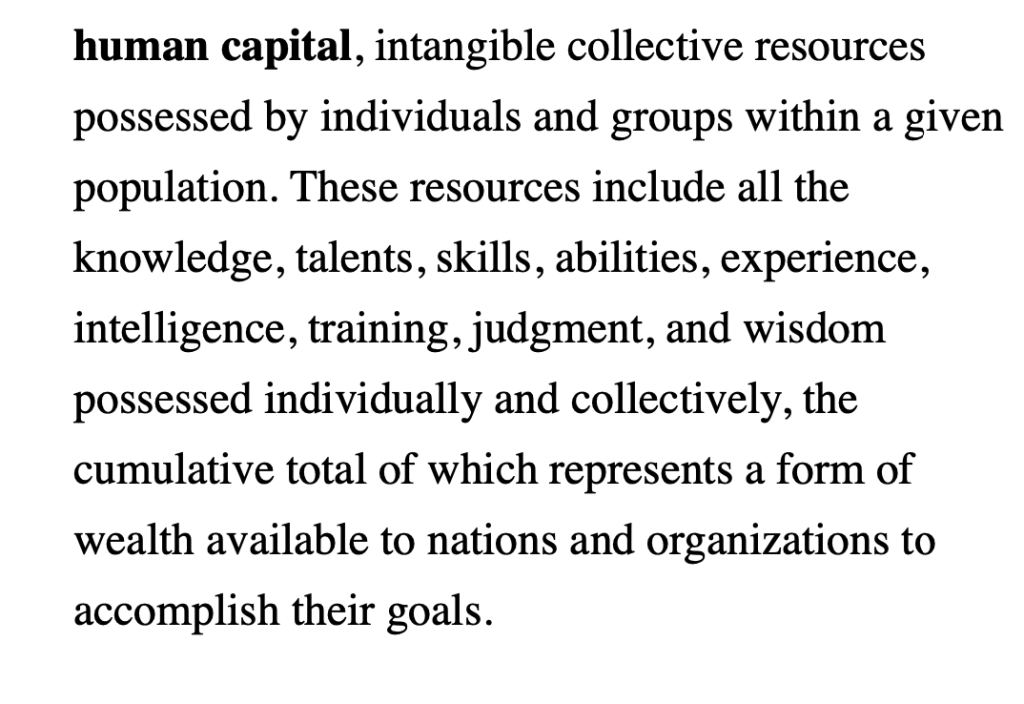

Before delving into the specifics of the California and Montana territories, it might prove helpful to assess Doepke and Tertilt’s understanding as to why the need for human capital led men to give women economic rights in the 1800s. The authors state, “the ultimate cause of the expansion of women’s rights throughout the nineteenth century was technological change that increased the demand for human capital.”[5] Furthermore, Doepke and Tertilt remark: it is essential to remember that before the 1830s, married women had no property, earning, parental, or divorce rights in the United States. All these economic rights were given to women by men and “passed by all-male legislatures that were accountable only to male voters,” note the authors. So why did these men choose to voluntarily give up their power over their wives? Doepke and Tertilt argue that it was “a trade-off” since women became the primary nurturers and educators after the industrial revolution. It would benefit the husbands to have their children married well to other equally educated citizens.[6] It is this trade-off that Anthony Carilli calls the “economic way of thinking.” He states, “all social phenomena emerge from the actions and interactions of individuals who make choices after weighing cost and benefits to themselves.”[7] Through this lens one can see how and why women’s economic rights increased throughout the postbellum economy.

The California Gold Rush and Human Capital.

John Marshall’s discovery of gold in 1848 led to a frenzy of males (predominately white) seeking their fortunes on the shores of California. This influx of men, comments Hurtado, created an economic scarcity of middle-class white women. This scarcity can be seen in the United States census reports at that time; Males per females in 1850 were 12-2, and by the time the census reported in 1864, the ratio was 3-1 for males and females aged 20-29. [8] Hurtado states that in this climate, “the scarcity of women tended to raise their economic value.”[9] Women’s work in this economy, says Hurtado, had vital value for the men of California. This included cooking, cleaning, sewing, rearing children, and adding to the family income through other means as well. Utilizing the letters from Methodist minister Henry B. Shelton, Hurtado notes that Shelton’s wife Priscilla “took in more than $300,” one month for teaching Sunday school, a select school, hosting a boarding school, and giving guitar and piano lessons, compared to that of his $12-15 dollars a week in offerings collection.[10] Women had real economic value and as such the men of California needed to find ways to increase the marriage market due to the lack of supply. One way the men of California did this was to liberalize divorce, giving women economic legal rights. Hurtado notes that the “dissolutions of marriage are best understood in economic rather than feminist terms…the general effect of liberalized divorce was to redistribute scarce resources—women—in the competitive and inflated gold rush economy.”[11] It was not for egalitarian or feminist reasons that women were granted economic rights in California but through an economic mindset, men traded off their legal rights over women to solve a scarcity problem and reap the benefits of human capital.

Human Capital and Montana’s Divorce law

Similar to California, women’s economic rights increased in Montana throughout the nineteenth century. Paula Petrik compares the roles of two cities–Helena and Butte—in advancing Montana’s divorce laws. Petrik notes that both cities started as mining cities in 1865 and averaged around 3,500 residents each by 1880.[12] Petrik notes that Montana’s mining cities had a similar economy to California and Colorado. As such, its lawmakers adopted similar laws and grounds for divorce as those states.[13] By the early 1870s, women had gained considerable economic rights. They were allowed to divorce for many reasons, including “impotency, bigamy, adultery, abandonment for the space of one-year, willful desertion, habitual drunkenness, extreme cruelty, or conviction of a felony or infamous crime.” Male lawmakers in Montana saw the economic reasons for allowing women to divorce, and like California, they created liberalized divorce laws to redistribute the lack of supply in the mining towns and decrease the amount of “welfare machinery needed to deal with abandoned or battered wives…when the opportunity arose to resolve a domestic problem, create the possibility for a new, more stable household, and reduce welfare rolls,” the magistrates accommodated.[14]

In conclusion, women’s economic rights grew in the postbellum economy due to changing roles of human capital, where men freely diminished their rights over women to meet specific economic supply needs.

[1] United Nations Development Programme, “Human Development Index (HDI),” http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi.

[2] Paula Petrik, “If She Be Content: The Development of Montana Divorce Law, 1865-1907,” The Western Historical Quarterly 18, no. 3 (1987): 261–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/969088.

[3] Albert L. Hurtado, “Sex, Gender, Culture, and a Great Event: The California Gold Rush,” Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 1 (1999): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/3641867.

[4] Matthias Doepke and Michèle Tertilt, “Women’s Liberation: What’s in It for Men?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics124, no. 4 (2009): 1541–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40506266.

[5] Ibid., 1543.

[6] Ibid., 1583.

[7] Anthony Carilli, “The Economic Way of Thinking-An Interview with Anthony Carilli,” (Feb 4, 2012), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJVEyNwNPI8.

[8] Kennedy, Joseph Camp Griffith, and United States. Census Office. Population of the United States in 1860. Washington: G.P.O, 1864. 22-30, Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926.

[9] Hurtado, 9.

[10] Ibid., 7.

[11] Ibid., 17.

[12] Petrik, 262.

[13] Ibid., 263.

[14] Ibid., 288.